Anduril: Fixing the Broken Sword of US Defense

Startup spotlight #14

Note: This is one of my favorites, and while I am 4-5 weeks behind, it is worth it. I had to get Anduril right. This company is just too important to not get right. If you enjoy this piece, please subscribe for further deep-dives just like this one! More to come!

The Russian invasion of Ukraine ended a one hundred year stretch of peace in Europe. Until that point, active war felt like a distant concept. War was something that occurred in different parts of the world, but in Europe? America? No way. Impossible!

Note: In my opinion, the dissonance between our reaction to war in certain areas of the world (e.g., Middle East, Africa) and our reaction to anything that hits Europe & North America is the true ethical debate we should be exposing; but save that for another day!

Rob Henderson has an interesting concept called "luxury beliefs." They are beliefs that act as a status symbol. Beliefs only someone from an affluent background could believe. In the process of having them, they actually poorly impact those less affluent. Believing freedom is a guarantee and war was is impossible is a "luxury belief." In many of our lifetimes, we have not seen it, but for many around the world, it is all they have seen.

Now, however, it became much more real. Defense and national security are more "trendy", but the previous decades of neglect have taken a toll. Today, the US Defense industrial base is fairly broken.

The Context: The State of US Defense

Here are four macro factors we should understand about US Defense:

The consolidation of defense contractors

The challenges of the private sector

The slowing pace of innovation

The rise of our adversaries

The consolidation of defense contractors

A wave of massive consolidation began in the defense industry starting in the 1980s. In 1993, defense secretary William Perry told defense contractors that the post-Cold War environment would reduce spend. It was unlikely defense spend could keep all of the major players in business. This dinner was known as the "Last Supper."

This harrowing realization led to a more acute wave of consolidation. By 2000, five the "Big Five" emerged: Lockheed Martin, Boeing, Raytheon, Northrop Grumman, and General Dynamics.

In 1990, only three of the "Big Five" were in the top-five for total share of US Department of Defense spend. Within ten years, the top five contractors increased their share of business from 21.7% to 31.3%, and they saw the total dollar values (both in 2016 terms) grow substantially (+50%). The weight of business has continued to consolidate. By 2020, the top ten contractors accounted for >50% of overall defense business.

While consolidation can improve efficiencies with scale, it has many downsides. In defense, it has dramatically reduced competition, and it has made the government increasingly more dependent on specific contractors. Consolidation has created a bit of a death spiral. In some cases, there are now only 1-2 potential US-based contractors competing to make a specific weapon on a military program.

The US defense industrial base has been consistently declining, and oddly, it is both fragile and ironclad. The system has many points of failure that rely on only 1-2 vendors. If they fail, what do you do? Simultaneously, those vendors are very sturdy, and often, they are challenging to disrupt. More importantly, the consolidation is reducing competition & innovation.

The challenges of the private sector

To combat this slowing innovation, the US DoD can actively turn to innovation hubs like research universities and the technology sector (e.g., FAANG). There would be a lot of historical precedence here. Much of early tech entrepreneurialism was inspired post-WWII and throughout the Cold War era. This created a whole wave of entrepreneurs building technology that pushed the DoD forward. In parallel, Federal investment in American research surged, enabling thousands and thousands of experimental programs.

This model has worked fairly well, but over the past decade, it has become increasingly challenging. Tech companies that have historically been the first to work with the DoD have either A) stopped supporting DoD programs or B) refused to work with the DoD entirely, citing "ethical concerns" from employees. For example, Google backed out of Project Maven due to employee petition.

In the paragraph above, I put "ethical concerns" in quotes for a particular reason. Much of these actions seem to be situational (Note: More on this later in the piece). For example, in parallel to heightened concerns about the ethics of working with our Department of Defense, here are two other actions companies are taking:

Engaging with Saudi Arabian government (ex., Stanford, Google)

Investing in Chinese infrastructure (ex., Apple to invest $275B in China)

The US Government pushed through $50B to bring more semiconductor production back the US. It is a huge investment in our infrastructure and national security. Apple invested 5x that in China...

These ethical debates do have merit. I would not discredit that. But the overall consistency is lacking. And to their defense, many of these organizations do want to work with the Department of Defense. Sadly, they just have to do it quietly.

Google is already backtracking their stance on working with the DoD. Stanford introduced a class on "Hacking for Defense", and while it did receive pushback, they stand by the overall positive impacts it is producing. Quietly, big tech has fulfilled hundreds of contracts with Defense. Finally, the Association of American Universities continues to lobby for significant research funding.

The slowing pace of innovation

As a result of consolidation and challenges in the private sector, the defense innovation has been decelerating for decades. Ben Rich was a former Lockheed Martin Skunk Director, and in his 1994 memoir, he said, "In my forty years at Lockheed, I worked on twenty-seven different airplanes. Today's young engineer will be lucky to build even one."

This is not just an isolated take. 25+ years later, Deputy Defense Secretary Kathleen Hicks voiced her concern on reduced defense innovation, yet the overall % of spend on R&D remains quite low.

While people in defense feel this, the data shows it. In Exhibit 4, there are three groups: 1) military aircraft, 2) commercial aircraft, & 3) auto. Measuring the time from concept to completion is a fairly good proxy for our building capabilities.

The time for autos has been declining. Since 1975, we have improved dramatically in how quickly we are able to create a new auto concept & build it. This makes sense. Our technology has improved dramatically.

Problematically, the timeline for military aircraft (#1) has almost 5x'd! Not only are we producing less models of military aircraft, but they are taking 4-5x longer. Imagine the implications here. If we want a competitive plane in 2050, we need to start designing it in the next five years. But how do you design a plane that will be top-of-the-line ~25 years in advance? Spoiler. You don't.

We will discuss incentives more, but at a high-level, the system does not incentivize research & development investment. At fast-growing tech companies, R&D can be +10-20% of revenue. At defense contractor, it is only 1-3%...

Sadly, that is where our DoD is. There is more AI in a Tesla than any military vehicles they use. Snapchat has better computer vision models than most of our military technology. The military was using floppy disks as recent as 2019.

The rise of our adversaries

In parallel, US adversaries like Russia and China have been investing heavily in their military. By many metrics, the US is still the dominant player in areas like Cyber (ex #1, ex #2), but increasingly, both China and Russia are gaining ground and becoming cyber threats.

Both countries are on a quest for AI superiority. Putin believes AI will rule the world, and China wants AI superiority by 2030.

In 1994, Ben Rich noticed the US military slowing. Since that time, China has +20x'd their military spend!

As a result, in simulations, China has made formidable progress. In 1996, the US would have a major advantage across 14 of the 18 scenarios. In 2017, that number dropped to two! It is now estimated there is parity across eight of those scenarios.

On the Russia side, we have seen continued reliance on aerospace technology (read my piece on Ursa Major), and we have fallen behind significantly on hypersonic technology. Instead of investing more, Congress cut spending on research designed to catch us up.

Slowly the power dynamic has changed. The attack on Ukraine was the first big step. Wars rarely start when it is clear one side will win. For example, if Russia knew that the US could end this immediately, a war would be less likely to break out. But with their nuclear capabilities, they know people will not directly intervene.

As China rises, geopolitical questions around places like Taiwan become more important. If the US was the clear dominant player, there would be no concerns of China invading Taiwan. But we may lose that battle. And they know that. So anything is on the table.

While the US government has made some egregious foreign policy mistakes in our history, we have on the whole had a better perspective on ethics than most (in my opinion). This has enabled us to speak out about human rights violations. But that's because of our dominance. As Palmer Luckey said, "To have ethical superiority, you need technical superiority." We are losing that.

The Problem: Fighting a 2000s war with 1900s methods

These large macro trends will continue to shift for the foreseeable future, and everyone should be very concerned. In my opinion, we have one huge misconception that is dangerous: when the war starts, we will jump into action just like we have in the past.

As Anduril founder, Palmer Luckey, said, "You go to war with the tools that you have, not the tools that you wish you had or the tools that you start working on when things become a problem."

A popular culture assumption that has been depicted in Hollywood movies and shows is that the US has a secret arsenal. When calamity hits, we will pull out high tech weapons that nobody has. The truth is... we are still using many weapons that are decades old.

The battles of those eras are way different of what the next war will be. It will be driven by autonomous vehicles, software, etc. Today, we have serious structural problems. Here are ten.

The way we build: Fighting battles of the past

Before anything else, let's first ask... are we building the right things? The F-35 is a great example of how we build. Big, expensive machinery and powerful machinery. We have a military built of (#1) the big and few. Aircraft carriers. Submarines. Fighter jets. Bombers.

These are all amazing, but they come with a wide set of problems (non-exhaustive):

Expensive: The 12-vessel Columbia class of US submarines is estimated to be $112B (Source). F-35's are estimated to be $75-100M per plane (Source). Creating these tools at scale is an incredible expense for Americans.

Time-consuming to build: These massive pieces of machinery are hard to make. For the F-35, there are 300,000+ parts with 1,100+ suppliers (Source). The design process alone can take a decade. This makes it very challenging to manufacture at scale + design machinery that has up-to-date technology.

Difficult to maintain & replace: Because of the expense and time to build, these massive pieces of machinery are very difficult to replace. At any point, only ~70% of US aircraft are mission capable (Source).

By the time they are built, they are likely outdated too. Think about Exhibit 4. We build these plans over 10-15 years. It takes years to produce volume. Then it hits the market 15-20 years after design. Systems are changing rapidly. 15-20 years is wayyyy behind.

Even then, these big pieces of machinery take multiple people (sometimes hundreds) to operate. Even if you could scale production, you might be limited by the number of pilots trained. The (#2) operator to machine ratio can be quite high.

Drones and unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) could help extend this, but today, many of them still require multiple people to operate. For example, the Reaper drone is actually highly human capital intensive. It only takes two to operate, but it takes an entire ground control station with many technicians. This comes at a time where the Air Force has a shortage of pilots.

The cost-plus model: I want my cake and eat it too

These massive pieces of machinery are incredibly complex, so designing, building, and operationalizing them takes years. For contractors, this is very daunting. A 15-20 year project is impossible to properly scope. For them, there could be unlimited cost downside. As a result, the industry created cost-plus contracts to mitigate risk. Unfortunately, this has had many adverse effects.

In a cost-plus contract, the contractor is paid for all expenses (cost) PLUS an additional fee. For example, let's say you ask me to build a fence. Rather than give you a price up front, I will just build the fence. In the process, I will keep track of the amount of materials (e.g., wood), the hours worked (labor), etc. At the end, I will add up all of the costs, and then I will charge you a premium fee on top of it.

Well, what happens if the fence takes ten hours longer than I originally quoted? Does not matter. You still pay me.

What about if I break some of the wood in the process? Does not matter. You still pay me.

Even if the quality is not great (within reason), you still owe me the price of the contract plus my fee. Ultimately, this leads to a variety of problems. First, contractors are incentivized do (#3) more work instead of good work. More work means that contractors can bill more labor hours & materials.

They can charge a fee on all of it. Let's say the fee is 20%. If you complete the job for $200 of cost, then you only make $40 on top. But what if you complete it for $300? Then you get $60 in revenue. Exhibit 9 shows how the incentive is to drive budget up.

The incentive is to underbid projects, so you win them, and then just drive the budget up over time... increasing revenue.

Surely, if contractors did this every time, the US Government would hire someone else, but... recall Exhibit 2 & 3. Who can they call? The industry has very low competition. Not only that, but the switching costs are high. Once the government has invested billions in your project, it is quite challenging (logistically & politically) for them to shift away.

Take the F-35. The budget has already passed $1T!!! But put yourself in the DoD's shoes. If the budget has ballooned to $500B, you likely want to hold contractors accountable and go hire someone else. But how do you tell the public that $500B went to waste? It is hard. Instead, the contractor says, "we need just a few hundred billion more." So you do it. And the cycle continues.

Even worse, once the F-35 is complete, you have to buy them! Over the next 20 years, the US Government will continue to buy F-35's, and it will pour money into contractor pockets, despite their performance being abysmal. In the end, there is (#4) limited accountability for contractors

Ultimately, the contractors operate in a (#5) risk-free environment. They pass through costs. They are not held accountable. Businesses that are risk-free get complacent.

Startups are the paradigm for staying lean & innovating. This is a function of their risk. They have to take aggressive & thoughtful action or risk failing. But when you are in a risk-free environment, you are not forced to operate at a high standard. It is bad for everyone involved.

The current state: The insider's game

Building big items & cost-plus contracts means that each investment is MASSIVE. It has naturally created a (#6) slow & complex defense budgeting process. While central planning does have positives, keeping up with technology remains challenge.

This graph is very important. It shows the complexity of the system. Some notes:

Multiple cycles: At any given point, the defense industry is planning three different budget cycles (while executing another)

Planning in advance: The planning process begins 2+ years prior to execution event begins

Programming & budgeting: This process requires memorandums that project an additional ~3-5 years into advance

Not only is the Department of Defense planning A LOT at one time, but they are having to decide what to build ~5-8 years in advance. Imagine how fast technology is moving. How could you possibly do this?

And within each cycle, there is SO MUCH complexity. Here is a snapshot of what a lifecycle management might look like.

If you are having trouble reading, that is ok. I think everyone is. It looks like Clippy vomited on a PowerPoint slide.

This process is endlessly complex. Centrally planning it is a nightmare. It is very slow, unlikely to push innovation or build quickly, and very challenging for new entrants.

Which leads to the next challenge: (#7) barriers to entry. Capitalism relies on incentivizing outlier individuals to innovate & build solutions. Silicon Valley has used this model to build trillions in value.

Within defense, however, it is not so easy. Many of these initiatives are very resource intensive, so they are very expensive businesses to start. Landing a big government contract can help that, but that is very challenging.

It is lower difficulty to find <$10M deals from leftover budget. In some cases, that could be in the $10-100M range as well. As you start approaching these massive defense deals, the level of difficulty increases dramatically.

The DoD is unlikely to work with a company they fear may go out of business. Once you get your foot in the door, companies still need product vision and a strong balance sheet. This is challenging for new venture entrants.

Finally, there are additional requirements like Sensitive Compartmented Information Facilities (SCIFs). Without these, then you cannot do classified work. In order to get them, you often need to have classified work. It is a bit of a chicken / egg problem. Large players can repurpose SCIFs. This makes the entire process much easier.

The complexity, speed, and high barriers to entry are further strengthening the grip the Big Five have on the industry. The wave of consolidation is not over, and in today's industry, it essentially (#8) functions similar to an oligopoly. Russia is not the only one with Oligarchs!

Now, some might refute this claim, and maybe it is unfair. But the definition of an oligopoly is, "a market structure with a small number of firms, none of which can keep the others from having significant influence." The top five firms have A LOT of influence. Now, the counterfactual is that they only do +30% of the share of business and contracts (See Exhibit 2). That mean 60-70% of business is done by others.

On the surface, this may not look like an oligopoly. But when we look at Exhibit 3, most of the defense subsegments are consolidating and approaching only 2-4 players within each space. Each functions as a small oligopoly with significant influence.

The private sector: Let's all just optimize ads

All of this can be reversed. No country can move & innovate like the United States, but (in my opinion) that requires the best & brightest minds. Sadly, the defense industry has been suffering from significant (#9) brain drain.

Inherently, 10x engineers & operators move much faster than the status quo. If they are unable to, most will get frustrated and move on. Now, imagine a space as slow as defense (for all of the reasons mentioned above). Not to mention, Silicon Valley has produced hundreds of thousands of high-paying, fast-moving jobs. As a result, talent has been flowing to ads optimization, emojis, filters & B2B SaaS.

These businesses have brought tremendous wealth to the United States, so I do not mean to disparage them. Unfortunately, an indirect downside has been a brain drain from traditional industries that really need the top-tier, innovative talent.

Finally, defense carries some extra baggage with the (#10) ethical debate around the work. These debates are 100% valid, and if someone feels morally conflicted, then I would never try to override those feelings. In my opinion, most situations often have a combination of naivety, hypocrisy, and selective , but in my opinion, situational hypocrisy. Here are some examples:

Naivety: The assumption that we have the unilateral ability to define the standards of war. In reality, while our best may refrain from building drone warfare, our adversaries will not.

Situational hypocrisy: We are quick to say our top businesses should not be arming our military, but we allow our businesses to invest & our consumers to buy from nation states with severe ethical concerns (like China, UAE, etc.)

As a result, our private sector talent is heavily indexed on optimizing & B2B workflows.

Note: This is something I think Tesla & SpaceX have changed; piece coming in the future from me!

The Solution: The Flame of the West

In the Lord of The Rings, Aragorn uses a sword called Anduril. The sword is also called the "Flame of the West" or the "The Sword That Was Broken". Both of these alternate translations should tell you everything about the vision Anduril founders Palmer Luckey, Trae Stephens, Matt Grimm, Joe Chen, and Brian Schimpf have in mind (Note: Contrary does a great job covering founding story here). They have set out to reinvigorate the US & allied military & fix a broken system.

We will cover a few topics here:

The vision

Pushing the limits of innovation

Designed for real-world missions

Interoperability

Assuming the risk

The future of defense

The vision

Fundamentally, Anduril has an entirely new vision of how future wars will be fought. Instead of multiple soldiers to one machine, there should be one soldier controlling many machines.

Amazing. The end result is a futuristic defense platform that allows a soldier to see the entire battlefield, receive alerts of threats, quickly assess options, and act. But how? Software.

Anduril has a pretty basic defense framework: i) understand, ii) decide, and iii) act.

Understand the threat. Provide information and recommendations to soldiers. Allow them to decide on course of action. Then act. But this all begins on understanding, which requires information.

Anduril has an entire suite of products that serve a specific purpose or function. All of these products are intelligently designed to be attritable & adaptable. They all leverage Anduril's core software platform: Lattice OS.

Consider this. In previous days, you may have humans looking at monitors & "keeping watch." Think of a security guard with 20 screens. That can be hard to track, and it requires pure attention... something humans are not great at. Imagine scaling that to thousands of devices & complex landscapes, plus requiring someone to triangulate drone + sensor information... it is impossible for a human to do.

Lattice triangulates all of the information of these hardware devices and sensors, and it creates a real-time 3D view of the landscape. Not only that, but it uses intelligence & automated workflows to surface key decisions for the operator. This reduces cognitive burden, and it enables the operator to focus on areas that require human decision-making and judgement.

Pushing the limits of innovation

Lattice is the backbone of the entire platform, but the hardware itself is pushing the limits of innovation. Consider these facts:

Ghost: 37lb drone capable of customization; can be assembled & flown by a single operator in less than three minutes; capable of 55 minutes of flight time, and a single operator can control multiple

Agile-Launched Tactically-Integrated Unmanned System (ALTIUS): Launched from a tube, enabling launch from vehicles, aircraft, boats, etc.; Can fly for 3+ hours

Dive LD: 3-ton autonomous submarine that can operate for up to 10 days, travel 300+ nautical miles, and dive 6,000 meters deep.

Sentry towers: Can be built, deployed, and connected online in less than three hours; very customizable within different terrains

Wide-Area Infrared System for Persistent Surveillance (WISP): Provides 365 / 24/ 7 alarm-based security to a single operator; passive (no signal) system means it cannot be jammed or detected; can be placed on towers, vehicles, boats, etc.

Dust: 4lb sensor that can be rapidly deployed; sensor detects people & relays to sentry towers; battery can operate sensor for up to two months, but solar panel provides indefinite operations

Menace: an expeditionary command, control, communications, and computing (C4) platform; shipping container that is versatile, temperature regulated, and SCIF capable.

The rate of innovation is stunning, and it will only increase. Anduril tests at a rapid pace. They are applying typical software test & learn speeds to hardware. Their first prototype shipped in three months. Their manufacturing abilities and scale are ramping. Here are some anecdotes of Anduril's speed:

Anduril was founded in 2017; the first pilot program with a customer occurred in 2018

Anvil was first sketching in late 2018; by mid-2019 they had a working prototype; by 2022 they were awarded a Systems Integration Partner contract with SOCOM. Whiteboard to one-billion dollar program in 31 months!

Menace went from prototype to launch within six months

Designed for real-world missions

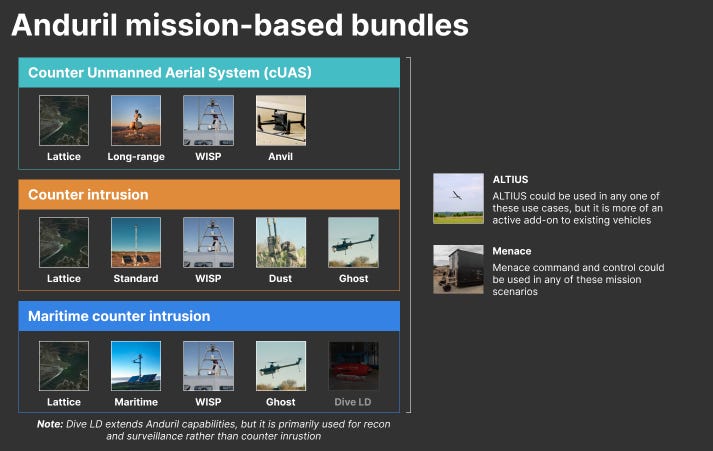

This product suite is not just by accident. Anduril is building and designing intelligent hardware that is specifically designed to solve key solutions. These devices can be pieced together to solve specific missions:

The power of Lattice and the platform really comes to life when you consider the step-by-step of how this plays out.

More importantly, Anduril builds these devices with versatility & customizability. This makes them very easy to innovate on & repackage for new missions. As new mission arises, they can quickly design and build for that specific need.

Interoperability

As Anduril expands their missions, they will have more devices flowing into Lattice. This is a network effect. Lattice will continue to improve as the number of devices and amount of information increases.

For this reason, it is designed to be able to integrate with new devices. This is critical in three places:

New product development

Acquisitions

Older military assets

The first is the easiest. As Anduril builds new products, it will be quite easy for them to design them to operate with Lattice.

The second is slightly harder. Over the past two years, Anduril has made a few acquisitions.

Dive technologies → Dive LD

AREAI → ALTIUS

Copious Imaging → WISP

These are all core solutions to their missions above. In some cases, it may make more sense to build vs. buy. For Dive, Area-I, and Copious Imaging, joining Anduril brings a lot of benefits. They can plug into a large platform (Lattice), improving their capabilities. Also, they can join a strong business development department that can help them land government deals. But none of this works if they cannot leverage Lattice and plug into a larger ecosystem.

Finally, there is a third segment. What about all of the drones, sensors, etc. that the military already has. What do they do there? One of the hardest lifts for Anduril is bringing some of this old technology online. In some cases, they are quite literally working to get 40+ year old technology feeding information into Lattice (Example: Navy exercise)!

Assuming the risk

All of this operating is critical because Anduril has ditched the cost-plus model. Their job is to make valuable products and sell them accordingly. For that reason, they take a more Silicon Valley-esque approach. They spend their own money on Research & Development. As mentioned, most contractors only spend ~1-3% of their revenue on R&D. That is tiny. Anduril spends more than 50%!!!! In parallel, they have been taking venture capital funding to help scale.

Assuming the risk means that Anduril needs to be much more resource and capital efficient. They need to have much more conviction on what & why they build. All things that will lead to better outcomes for our military.

The future of defense

Earlier in the piece, we talked about the ten systemic problems in US defense. If we revisit them, we can see how Anduril is solving & managing many of these problems.

Anduril is redesigning the way we defend by replacing (#1) big and few machines with smaller, more agile, & more attritable drones. This is increasing the pace of innovation, reducing costs, and making militaries more dynamic.

To control all of these drones, Anduril has designed a platform called Lattice OS that enables us to flip the (#2) Operator per machine ratio. Instead of five operators flying one drone, a single operator can command 5, 10, 15, 20+ drones & sensors. Maybe even hundreds.

By assuming the risk, Anduril is flipping the entire cost plus model. They cannot rely on (#3) more work > good work because that will eat at their margins. They cannot operate under the assumption of (#4) limited accountability because delivering results will be their competitive advantage. They cannot operate (#5) risk-free because they bare all of the risk.

The industry problems cannot be solved, but they can be managed. Anduril navigates the (#6) slow & complex budgeting process by competing across all three tiers:

Short-term: Win leftover and ~$5-10M contracts by delivering immediate value with current solutions; interoperability allows them to bring existing assets online

Medium-term: Develop holistic mission-based use cases that win larger contracts on 1-2 year horizon

Long-term: Invest in R&D & business development to win massive contracts for the future of defense

They do all of this... in parallel.

Anduril is actively acquiring companies (e.g., Dive Technologies, Area-I). This enables these companies to be plugged directly into Anduril's business development. This leads to consolidation, but as they all succeed, the (#7) barriers to entry should continue to reduce., Anduril's success paves the way for more defense startups and innovators to breakthrough. A rising tide lifts all ships. This should put significant pressure on the (#8) oligopolies.

All of this success, innovation, etc., is helping with the private sector. 10x engineers want to be in places that matter. Increasing the speed of innovation in defense will dramatically improve (#9) brain drain. Recent geopolitical movements have also increased passion for many in working in this space.

The (#10) ethical debate is much more complex. I would never diminish how someone feels about this stuff. It is a very serious topic. I will, however, present some themes that I hear in Stephens & Luckey's interviews:

American Ethical Superiority - The US military has made MANY mistakes, but on the whole, America has been historically on the right side of ethical debates. If not in the moment, the long-term general trajectory has been positive, particularly when compared to our foes

Technical superiority is needed for ethical superiority - Our ethics do not matter internationally if we do not have technical superiority

Humans make the decision - We can automate processes & use AI to improve the tools we have to make decisions, but ultimately, humans should remain in the position to make decisions with any ethical concerns

Focus on defense - The primary focus & boundary on work is to improve defending national interests, not creating the biggest offensive firepower possible

Conclusion

People may think I wrote about Anduril because it is trendy. It will get clicks. They have been successful. The brand is sexy. Sure, this is all great, but I actually wrote about Anduril because I think this company really matters.

Recent generations are some of the first to forget the importance of defense. We have not truly needed to live it, particularly in the US. Regardless of your stance on Anduril, it is critically important that we have entrepreneurs, leaders, innovators, etc. pressuring our public institutions. Competition will push everyone to be more thoughtful. More efficient. More effective.

In the case of Anduril, they are doing it to an industry that needs it terribly and is incredibly important. For that, I am very thankful!

Appendix

One pager

Market drivers

Growth drivers

Geopolitical tensions - Increased concern around foreign aggression will certainly be used as a means to expand focus on defense

Progress in AI - Over the past few years, Artificial Intelligence has made significant progress.

Uncertain factors

Defense budget - The overall impact on defense budget is still TBD. Social pressures might have pushed it downward previously, but I think the geopolitical challenges will reverse that.

Risk factors

Social pressure - There are potential headwinds to the overall market as people pressure to reduce defense spend. That can be for ethical reasons, or it could be people arguing defense is generally overfunded.